I Hate You, Mother

Aurelia Plath believed (she was right) that Sylvia's psychiatrist ruined their relationship.

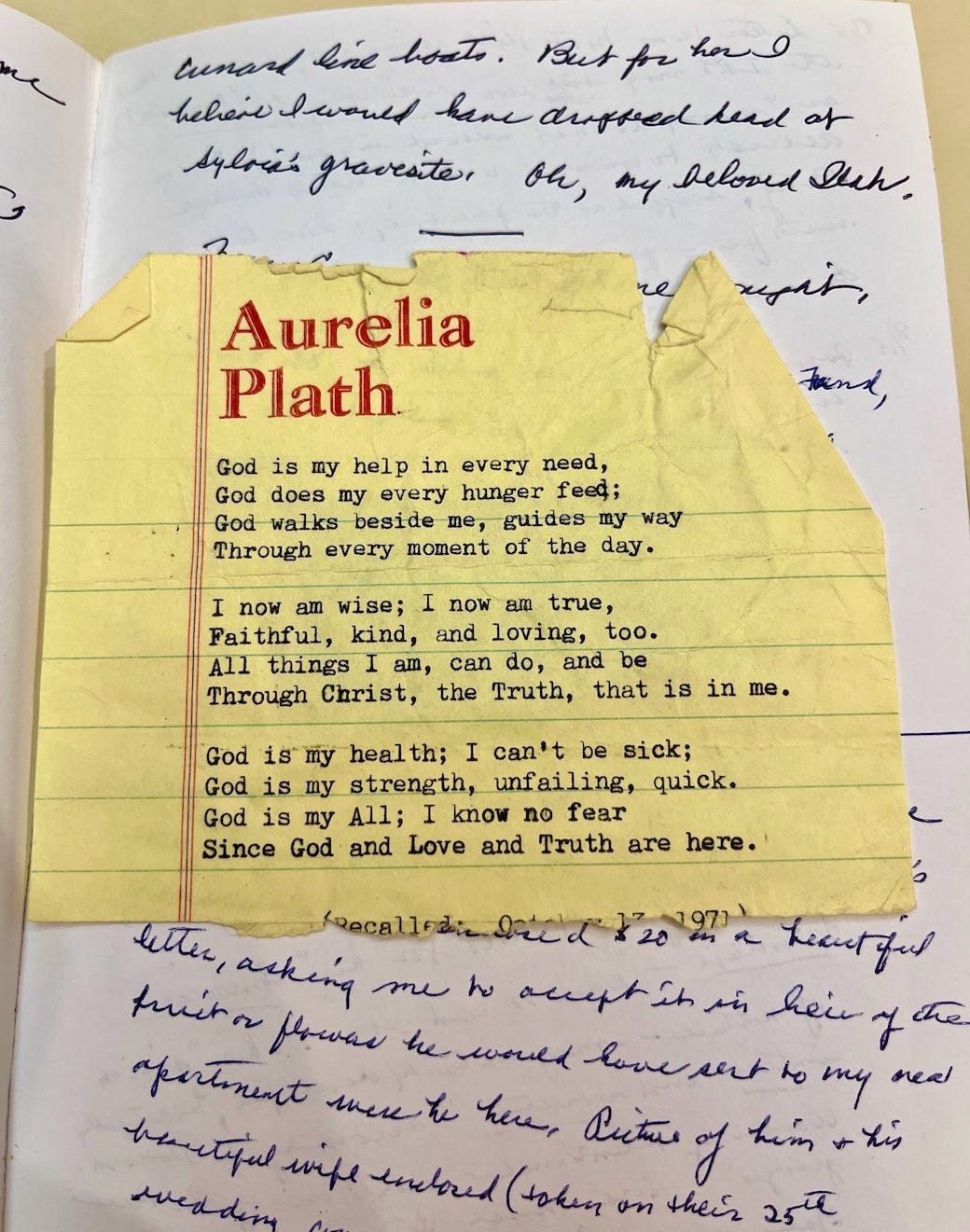

[Christian Science prayer found in Aurelia Plath’s diary, Beinecke Library, Yale. Sylvia Plath asked her mother for a copy.]

I’ve been avoiding writing about Sylvia Plath’s psychiatrist Ruth Beuscher, but it’s ruining my life so I’ll just do it. I found Beuscher is prominent enough in the Plath women’s letters/diaries/journals to pursue the question I haven’t found answered: What did this woman do, this psychiatrist whom Sylvia adored and Aurelia Plath despised?

I researched different facets of these relationships. Each woman had a lifelong effect on each. Get this: I hoped to write a “Three Women”-type radio play using what the Plaths and Beuscher wrote and what they said. Then I realized it was a vanity project – unless, unless, it said something new.

Dr. Beuscher was 31 when Sylvia Plath became her patient. Sylvia sang her praises. Beuscher replaced Sylvia’s own mother in Sylvia’s affections. Aurelia resented this. She had reasons:

“Dr. Ruth Beuscher, faithful to Freud’s horrible, possessive mother figure of the ’50s, did her unjust, persuasive work to ‘free’ Sylvia from a ‘possessive mother,’ which I had no desire or time to be. I had my mother & dad to be concerned about, a full-time, demanding teaching-counseling job for 29 years at B.U. – ended as an Associate Professor – trained medical secretaries as work in B.U. gave me free evenings to be home with my children . . .” [15 July 1987]

That was written 34 years after Sylvia began therapy with Beuscher. Yet Aurelia wasn’t over the fact that the psychiatrist twice made Sylvia say she hated her mother.

Aurelia wasn’t wrong. It did happen twice – to Aurelia.

When The Bell Jar was published in the U.S. in 1971 Aurelia Plath 1) had a heart attack and 2) took very personally the portrayal – really a sketch – of “Mrs. Greenwood,” who had a “pale, reproachful moon of a face” and didn’t understand her daughter “Esther.” Mrs. Greenwood nagged and snored and Esther’s impulse was to strangle her.

The abridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, published in 1982 and not fiction, said much, much worse about the real-life Aurelia, at length and in very personal terms.

Aurelia first read The Bell Jar in 1963 and was so shocked she denied her daughter had written it. She couldn’t stop its U.S. publication. For Aurelia it was tragic that The Bell Jar and the Journals were bestsellers, and the “hate my mother” passages, although limited, were their juiciest must-reads and the books’ emotional centers. And persuasive. Didn’t matter that The Bell Jar was fiction: Readers and critics believed Sylvia hated her mother. Criticism and scholarship have proceeded on that basis.

Aurelia saw it all happen. She felt as if Sylvia had thrown acid in her face. Publishing Letters Home and inserting in the Journals a mitigating note above its most savage entry only made matters worse.

Ever since Ariel in 1966 Aurelia dreaded the release of new Plath books that brought her – a private citizen -- unwanted publicity. Suddenly she was the world’s most famous mother of a suicide. In town and at work she got side-eye. People phoned asking if Sylvia’s father was really a Nazi. The Bell Jar brought to her door strangers seeking tea and counsel or wanting to see the basement. Aurelia was blamed for her daughter’s mental illness. She was libeled and defamed, but you can’t sue a dead person or an Estate you made a deal with.

Linking the “hate my mother” scenes was the psychiatrist, who in real life had treated Aurelia like a pest.

For Dr. Beuscher, Sylvia Plath was a very sad episode. Beuscher kept Sylvia’s letters, re-read them, and grieved. But Sylvia was not her only patient and Beuscher had to move on. About Aurelia, Beuscher did not give a fig, refusing to answer calls and letters. Aurelia’s diary says she only wanted to say that Sylvia’s family had always loved her, coddled her, and never pushed or exploited her. (“Always” and “never” are like smoke signals; I do see them.)

Sylvia in her journal celebrated Dr. Beuscher as the “midwife to my spirit.”

I think it worked both ways, and the word “spirit” is key.

Beuscher held great power and sway as Sylvia’s substitute mother and a role model. A rare female in a men’s profession, Beuscher was brilliant, attractive and stylish, wise, centered, and sex-positive. Like Sylvia she’d been a child prodigy. Also Beuscher was married and in 1953 the mother of three, and by 1960 the mother of seven.

In 1954-55 Sylvia had therapy with Beuscher when she could. In 1958-59 they had weekly sessions. Some of that time Beuscher must have been pregnant. In December 1957 Beuscher’s children were ages 6, 4, and 2-1/2, and another child was due in March. “Earthy Dr. Beuscher,” Sylvia wrote. One of the outcomes of therapy in 1959 was that Sylvia, 26 and married, decided she must have a baby. Sylvia told her journal she’d like four in a row. She did not say “just like my psychiatrist.”

When Sylvia died Dr. Beuscher was 40 and soon felt moved to radically change her life.

It took five years but Beuscher got a divorce in 1968, took her five younger kids and under her birth name Ruth Tiffany Barnhouse you’ll find numerous books and articles she wrote as a specifically Jungian psychiatrist (specialist in “depth psychology”).

In 1970 Plath researcher Harriet Rosenstein met Barnhouse for an interview. As with Sylvia, Barnhouse drew Rosenstein into a personal friendship. Rosenstein’s journal records that “Ruth” was obsessed with astrology and Tarot cards and tried to teach her. She took Rosenstein to an astrologer to help her “find the real Sylvia.” Rosenstein wrote up the result in her journal but redacted that entry. I’d love to know what it said.

To be fair, astrology and Tarot cards (and witchery and whatnot) were then in the Western cultural mainstream and their complexity and symbolism appealed to intelligent people. Sylvia and husband Ted Hughes had practiced those arts. So Barnhouse reading cards was not so very odd.

Barnhouse also attended an Episcopalian church. Volunteering as a counselor she met congregants troubled by spiritual and religious matters. Now and then someone thought they were Saint Mary or saw Jesus in a tree, problems too serious for a minister to handle. Barnhouse enrolled in a theology course to figure out “when the shrink should call the minister and the minister call the shrink,” and formulate the first such guidelines.

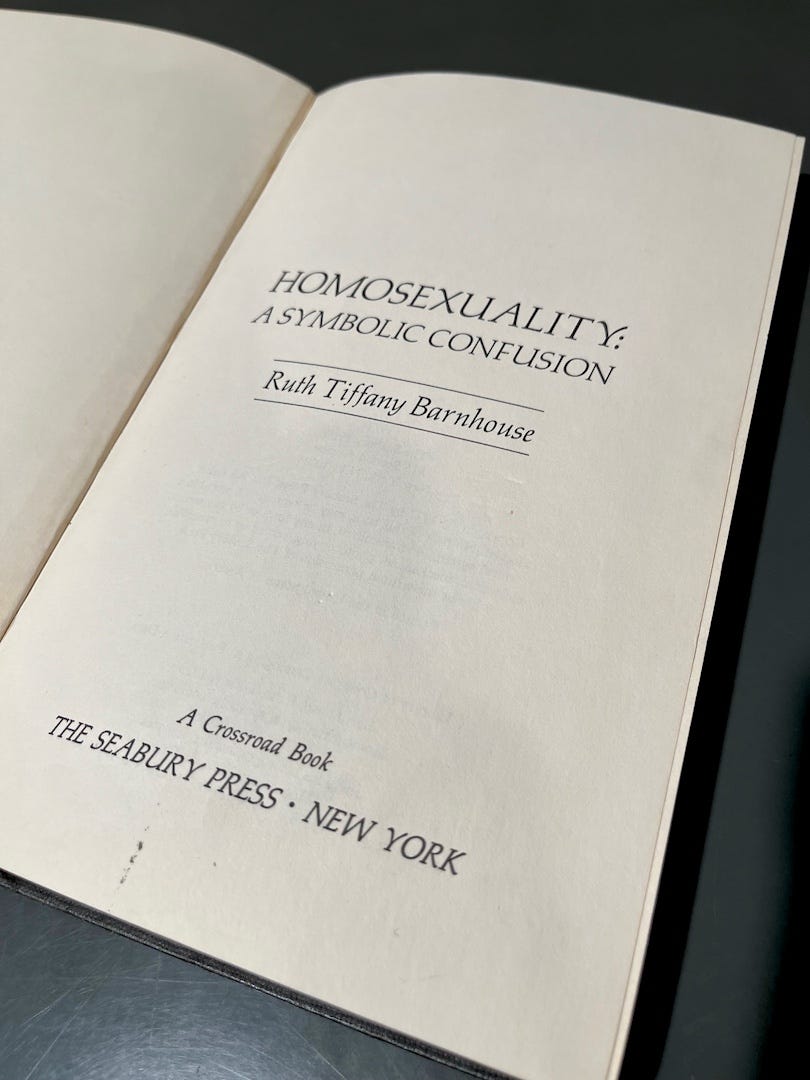

[Ruth’s book (1977) said homosexuals are immature. There was controversy. Washington University Libraries]

Freud had made fun of religious faith and rituals: A longing for God was only a longing for a father figure. Barnhouse realized that for the sake of her job she had repressed her interest in religion and spirituality, a sector of human experience her medical training taught her to ignore. She said, “Just like repressing anything else, this was not going to lead to any good.” As M.D. and then M.Div. Barnhouse wrote and published articles and books with a Christian perspective, smartly argued and thoughtful except for Homosexuality: A Symbolic Confusion (1977), an outlier because her other writings lean liberal.

Yet people are more than what they got wrong. Barnhouse went on to write solid feminist critiques of patriarchy – “the old cultural clothes do not fit anymore” -- and religious fundamentalism:

-I was brought up to believe that only Christians have the truth. I have not believed that for many years. I now see religion as a language with which people try to make some connection with the Ultimate Reality.

Barnhouse in 1980 was the first woman ordained as an Episcopalian priest. Around 1981 Fran McCullough, Aurelia’s former editor and friend, phoned Aurelia to say she’d lunched with “Ruth” and that Ruth was now a minister and “crazy.”

Barnhouse had felt moved to return to her roots. Nothing wrong with that. The taproot was her Presbyterian minister father, famous for strict fundamentalist preaching. She said about her childhood:

-When I and my brothers and sister were growing up, we knew that there were some people who talked about evolution, but my family’s collective representation was such that this idea wasn’t worth thinking about. Our collective representation was that Bishop Usher had established that the world was created on Thursday, October 23 at 9:00 a.m. in 4004 B.C. We all knew it was a fact.

-My father’s style was a cross between that of a Talmudic scholar and that of a Jesuit. We had had a graded Sunday school at the church where we had to memorize the Bible -- as much as a chapter a week in high school – and write a weekly essay.

Ruth’s grandmother was Jewish but it hardly mattered. By the time Ruth was eight her father broadcast a weekly “Bible Study Hour” coast-to-coast and did so until he died in 1960. He wrote and published twenty books about godly living. He founded his own magazine: Eternity. Recordings of his sermons persist on religious websites. I listened to one and my brain just fried: California-born Barnhouse affected a Scots/Irish brogue that comes and goes. Those who knew Donald Barnhouse in college and as a young missionary recalled his “elasticity of conscience” (braggadocio and lying). He was six-foot-two, overstuffed with personality, yet an expert on the Bible who gave sermons vivid and inspiring. A man of God. Meanwhile he had his four children rigidly home-schooled and all were prodigies: Ruth qualified for Vassar College at 14 and her brother at 17 got his degree from Harvard.

Ruth’s mother, nee Ruth Tiffany, had a master’s degree, but did not stand up to her husband (how could she?), and daughter Ruth had despised her for that. Sylvia Plath had the identical complaint; her father Otto had ruled their household with rages and commands and her mother was a jellyfish.

Both Ruth and Sylvia found it hard to forgive -- their mothers.

[“I don’t hate you, Mother.” Aurelia Schober in 1909, age 3.]

Aurelia Plath had heard Dr. Beuscher had mother issues and “an avid interest in telling about it,” and thought Beuscher coached her patients to hate their mothers too. One can see why Aurelia might think that. She was angry. But weak-willed and craven Aurelia was not. She wiped the acid off her face and went on living.

Aurelia’s later diaries have pages and pages of revolving complaints how the Hugheses, biographers, Dr. Beuscher, and the world ought to view her as a loving, giving mother and how unfair and hurtful it was that they did not. Aurelia addressed every criticism made of her, down to denying she’d ever said “lock, stock, and barrel,” saying Sylvia had said it. Inwardly Aurelia replayed at top volume every slight or unkindness or betrayal, and I don’t see that she considered the source. I don’t say “perceived” unkindness or betrayal; I’ll grant her the slack to decide for herself.

While writing only once of her pride in Sylvia’s Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, Aurelia recalled and relived the “greatest hits” of the many slights past, and defended herself -- as if anyone cared. Her earlier diaries aren’t like that. Yet for Aurelia the slights and hammer blows were ongoing and mounting because they were in print, attracting new readers and critics every day.

When her daughter Sylvia was wronged, Sylvia didn’t do much better. She wrote to Dr. Beuscher, who stopped answering.